#EconomicPolicy

#EconomicPolicy73

#CovidEconomics

Evaluating The ‘Swedish Solution’

The health and economic consequences of light government intervention in a pandemic

Private economic incentives are an important mitigating force in the face of a global health pandemic, as illustrated by new research evaluating the ‘Swedish solution’ of letting the epidemic play out without much government intervention in the form of lockdowns and other social restrictions.

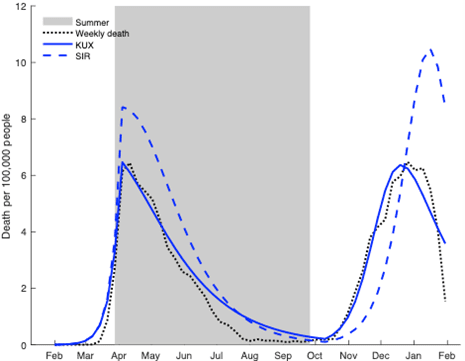

The study by Dirk Krueger (University of Pennsylvania), Harald Uhlig (University of Chicago) and Taojun Xie (National University of Singapore) shows how individuals shifting their consumption behaviour away from the most contagious activities can lead to substantial mitigation of the economic and human costs of the pandemic. As Figure 1 shows, the reallocation of economic activity to less infectious sectors slows down the epidemic and reduces the number of weekly deaths in Sweden from around 8 to 6 weekly deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, at the peak of both the first and second waves.

The research also suggests that varying infection risk due to seasonal forces or new virus variants could be a key explanatory variable for second and third waves in other countries, aside from variations in the stringency of lockdowns and the like.

Figure 1: Weekly deaths from Covid-19 per 100,000 people in Sweden from the beginning of February 2020 to the end of January 2021, actual and predicted from a purely epidemiological model (SIR) and one that combines epidemiological and economic forces (KUX)

More…

The Covid-19 pandemic of 2020-21 has the world in its grip. Policy-makers wrestle with the difficult trade-off between the economic pain imposed by lockdowns versus possibly risking many lives when those restrictions are lifted.

The policy response to the disease outbreak in the early spring of 2020 was swift but varied, but only a few countries have chosen to impose at most light government interventions and restrictions. Perhaps the most pointed example in the latter group is Sweden.

The new study evaluates this Swedish solution in the context of a model laboratory that combines an extension of the epidemiological SIR model describing the evolution of the disease with an economic model in which individuals make rational decisions how much to work and in what sectors of the economy to consume.

The authors use this model to argue that endogenous shifts in private consumption behaviour across sectors of the economy can act as a potent mitigation mechanism during an epidemic. When goods are distinguished by the degree to which they can be consumed at home rather than in a social, contagious context, individuals will shift their consumption behaviour away from the most contagious activities, possibly mitigating the spread of the pandemic.

Figure 1 summarises the results. It shows the weekly deaths from Covid-19 per 100,000 people in Sweden from the beginning of February 2020 to the end of January 2021. The dotted black line shows the actual data, the blue-dashed line represents the prediction from a purely epidemiological model where individual adjustments of private consumption behaviour are absent, and the solid blue line displays the predictions from the model that combines epidemiological and economic forces.

The observed second wave necessitates a strong and exogenous seasonal component in the infection risk. The research thus suggests that seasonally varying infection risk could be a key explanatory variable for second and third waves in other countries, aside from variations in the stringency of lockdowns and the like.

A combination of a seasonal decline of infection rates in the summer (April-September) with privately optimal consumption choices in the face of a deadly pandemic in the model generates two waves of infections and deaths, one in late March and early April 2020 and a second in the winter of 2020-21.

It also predicts an economic recession in Sweden in the spring of 2020 in line with the empirical record, as well as a reallocation of economic activity away from certain sectors of the economy (such as restaurants) and towards other sectors (such as groceries). Without this reallocation, the recession in aggregate consumption would have been 3 percentage points deeper.

Importantly, as is clearly visible from the figure, the reallocation of economic activity to less infectious sectors slows down the epidemic and reduces the number of weekly deaths in Sweden from around 8 to 6 weekly deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, at the peak of both waves. The reason is that when confronted with an increase in infection probabilities in the autumn, rational economic individuals adjust their consumption behaviour: they consume and work less, and crucially, shift their consumption again towards less infectious sectors.

The resulting reduction in economic activity in the more infectious sectors keeps especially the second wave, which occurs in the winter when biological infection rates are high, somewhat in check, relative to the crisis predicted by the purely epidemiological SIR model. Therefore, private economic incentives are an important mitigating force in the face of a global health pandemic.

‘Macroeconomic Dynamics and Reallocation in an Epidemic: Evaluating the “Swedish Solution”’

Authors:

Dirk Krueger (University of Oxford)

Harald Uhlig (University of Zurich)

Taojun Xie (University of Oxford)