#EconomicPolicy

#EconomicPolicy74

Technology and Early Retirement Push Older Workers Out of Employment

Evidence from Finland

New research examines how technological change and access to early retirement pathways reinforce each other in pushing older workers out of employment. The study by Naomitsu Yashiro, Tomi Kyyrä, Hyunjeong Hwang and Juha Tuomala analyses data from Finland to show that the probability of leaving employment is higher for individuals who are in occupations with higher automation risks, and increases further for individuals who are eligible for early retirement pathways.

At a time when promoting longer working lives is an important policy objective across OECD countries to mitigate fiscal pressures from population ageing, these findings suggest the need for policy action. Reforms that tighten access to early retirement pathways can substantially extend the working lives of older workers exposed to high automation risks, while having little effect on old workers exposed to low automation risks.

The recent decision by the Finnish government to abolish the extension of unemployment benefits is likely to encourage older workers more exposed to technological change to work longer and participate in upskilling opportunities. Employers will also have stronger incentives to provide more training to older employees, who can be expected to work until their mid-60s.

More…

Across OECD countries, promoting longer working lives is an important policy objective for mitigating fiscal pressures from population ageing, notably increasing pension and healthcare expenditures. One barrier to increasing employment of older workers is that workers engaged in codifiable, routine tasks are prone to being displaced by computers and robots, a trend that may have been accelerated by the pandemic.

Older workers are particularly exposed to this risk because, with shorter remaining working lives, they have weaker incentives to acquire new skills that would allow them to switch to tasks that are less likely to be automated. They may instead choose to retire early when facing rapid technological change.

Another barrier is that a number of OECD countries have in place institutions that encourage early retirement, such as exceptional entitlements or looser criteria for unemployment and disability benefits reserved for older workers.

These two factors reinforce each other in pushing older workers out of employment. That is, older workers highly exposed to technological change are more likely to exit the labour market when they gain access to early retirement pathways. Alternatively, those having access to early retirement pathways are more likely to use them when they are more exposed to technological change.

The new study explores such a complementarity for Finland. The country ranks as the top performer in adoption of digital technologies in socio-economic activities, according to the European Commission’s Digital Economic and Society Index.

It also displays a considerably lower employment rate for older individuals than its Nordic peers. This is strongly influenced by the opportunity for early retirement through the so-called ‘unemployment tunnel’ – the combination of entitlement to regular unemployment benefits up to 500 working days, and extension of unemployment benefits until the retirement age, reserved for the unemployed aged 61 or more at the time their regular unemployment benefits expires.

The inflow into unemployment increases significantly about two years before the eligible age for the extension of unemployment benefits, which is the earliest time that individuals can access the unemployment tunnel. Several past reforms have raised the eligibility age for this extension, delaying the timing for entering the unemployment tunnel and thereby lengthening working lives each time. The government of Finland recently decided to abolish the extension in 2025 for individuals born in 1965 or after.

The new study combines Finland’s rich employee-employer database (FOLK) and three different OECD datasets capturing exposure to digital technologies at the occupation level: the risk of automation, the intensity of routine tasks and the intensity in use of ICT skills, all constructed from individual-level data of the OECD Survey on Adult Skills.

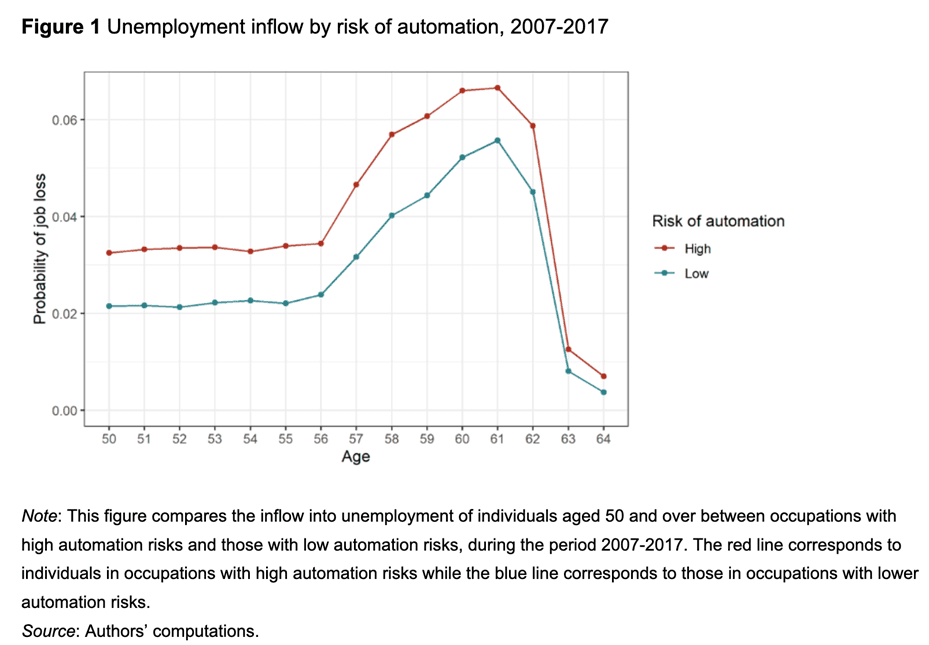

Figure 1 compares the inflow into unemployment between individuals in occupations with higher-than-average automation risks and those with lower automation risks during the period 2007-17, when the eligibility age for the extension of unemployment benefits varied between 59 and 61 (and thus the timing for entering the unemployment tunnel ranged between 57 and 59).

The unemployment risk is clearly higher for individuals in occupations with higher automation risks. Moreover, the unemployment risk increases faster for these individuals in their late-50s, as implied by the steeper slope of schedule. The difference in the unemployment risk between individuals with high and low automation risks is largest at age 59, when all individuals can access the unemployment tunnel.

The researchers then estimate the probability of an individual aged 50 or over exiting employment after two consecutive years of employment as the function of exposure to digital technologies, a dummy variable indicating the individual’s access to the unemployment tunnel, and their interaction.

They find that:

- An individual aged 50 or above in occupations exposed to one standard deviation higher than the average risk of automation faces a 1.1 percentage point higher probability of exiting employment every year, if he or she does not have access to the unemployment tunnel.

- This probability is 2.2 percentage points higher if the individual has access to the tunnel.

- Gaining access to the unemployment tunnel increases the exit probability of an individual exposed to an average level of automation risks by 1.8 percentage points.

- The overall impact of higher automation risks and the unemployment tunnel therefore amounts to 4 percentage points, which implies an 80% increase in the probability of exiting employment for individuals aged 57-58.

- The results are similar when using other indicators to capture the exposure to digital technologies, such as intensity in routine tasks or ICT skills.

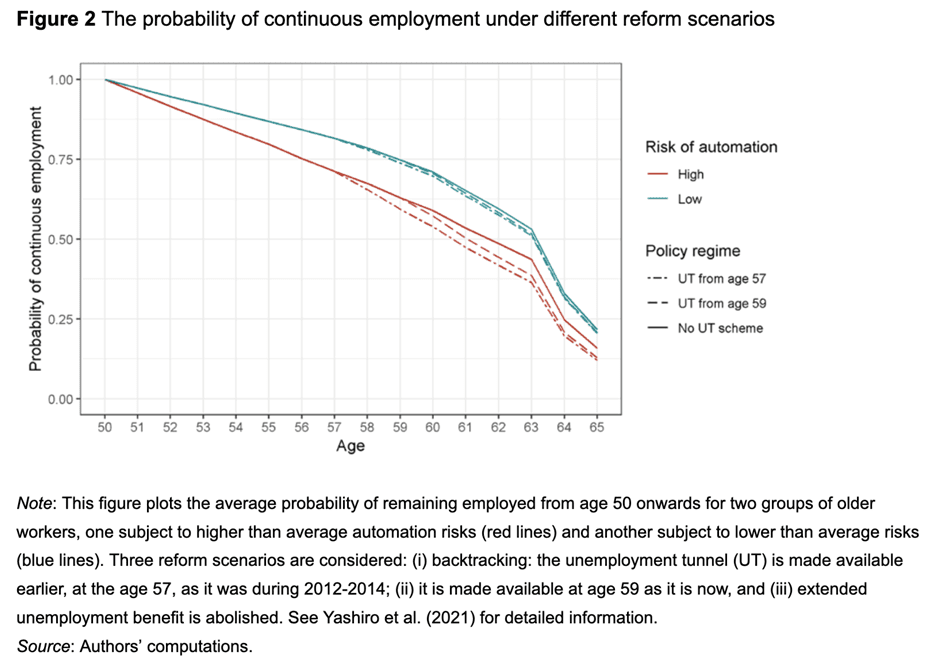

Using the estimated coefficients, the study simulates the impact of reforms that tighten access to the unemployment tunnel. Figure 2 illustrates that such reforms substantially extend the working lives of older workers exposed to high automation risks but have little effect on old workers exposed to low automation risks.

These findings underscore the importance of reforms that tighten access to institutionalised pathways to early retirement in ensuring the inclusion of older workers in the future of work. While previous policy discussions often emphasised boosting lifelong learning opportunities, older workers will only have weak incentives to take up such opportunities if these early retirement pathways are left open.

The recent decision by the Finnish government to abolish the extension of unemployment benefits is likely to encourage older workers more exposed to technological change to work longer and participate in upskilling opportunities. Employers will also have stronger incentives to provide more training to older employees, who can be expected to work until their mid-60s.

There is, however, a need for targeted measures to increase the employability of older workers most affected by the reform through highly tailored training programmes. It is also important to encourage older workers to participate in these programmes through better identification of their training needs, for example, through mid-career review or career guidance services, and certifying skills acquired through training.

Policy-makers should also ensure that measures to protect jobs and businesses under the Covid-19 crisis are not used as a fast track to early retirement. In Finland, the extensive use of the temporary layoff scheme prevented a large increase in permanent job losses. But some layoffs may have targeted older workers more exposed to technological change with access to early retirement pathways.

The new study presents preliminary evidence based on high-frequency data on unemployment inflows (including both temporary and permanent layoffs) that older workers exposed to higher than average automation risks experienced disproportionally larger increases in unemployment risks during the economic contraction, particularly at the ages when they can access early retirement pathways.

More details are here:

https://voxeu.org/article/technology-labour-market-institutions-and-early-retirement

‘Technology, labour market institutions and early retirement’

Authors:

Naomitsu Yashiro (OECD)

Tomi Kyyrä (VATT Institute for Economic Research)

Hyunjeong Hwang (OECD)

Juha Tuomala (VATT Institute for Economic Research)

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the OECD or of the governments of its member countries.