#EconomicPolicy

#EconomicPolicy73

#CovidEconomics

Inequalities in the Times of a Pandemic

Policy actions to address longstanding economic fractures

Covid-19 has exacerbated existing inequalities across multiple dimensions, including by region, by work sector, by gender, for children from different backgrounds and across the income distribution. New research by Stefanie Stantcheva (Harvard University, CEPR and NBER) summarises the evidence on some of the major inequalities that have been widened by the pandemic – and discusses avenues for policy intervention over the medium and longer term.

The inequalities that her study describes take many forms and express themselves along various dimensions. Across the income distribution, pre-tax income inequalities, consumption and savings, job losses and the opportunities for remote work have evolved very differently. Across genders and between parents and non-parents, the toll of school closures, lack of childcare and additional housework has been uneven. Across regions, sectors and occupations, the pandemic has brought vastly different burdens and opportunities. These fault lines also interact with each other.

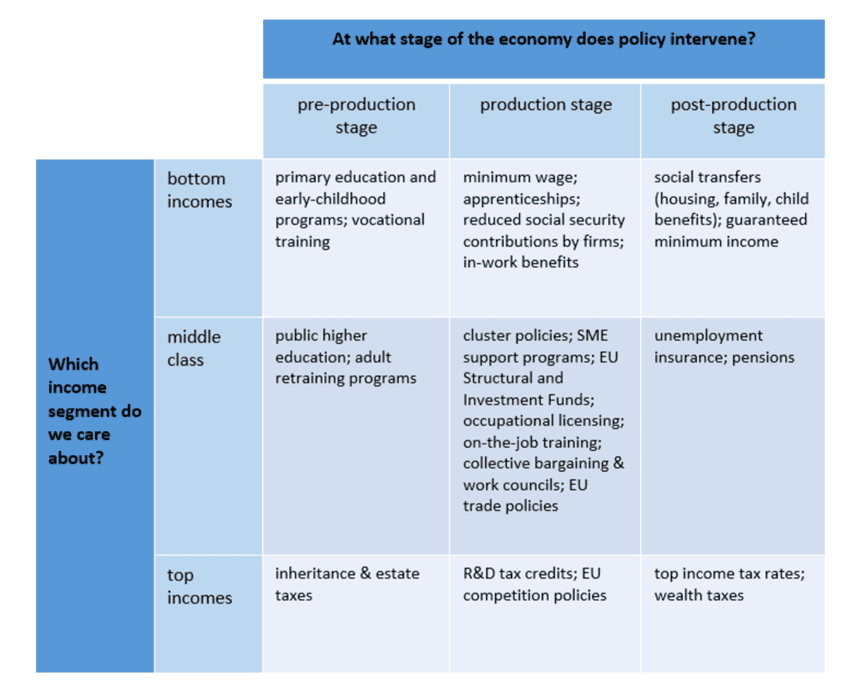

In terms of policy interventions to address the longstanding economic fractures exacerbated by the pandemic, Professor Stancheva presents a three-by-three matrix. On one side are the income groups mostly targeted by a policy: the very bottom of the income distribution, the middle class and the very top.

On the other side are the three stages at which interventions can take place: ‘pre-production policies’, which shape the endowments people bring to the labour market, and their opportunities; production policies, which influence firms’ decisions and how the labour market functions; and post-production policies, which are redistributive measures, such as government transfers and progressive taxation.

She concludes: ‘In a world in which middle-class “good jobs” are disappearing due to longer-run trends such as technological change and globalisation, and where shocks such as Covid-19 exacerbate the cleavages, there is a need to act on all three columns in a coordinated and comprehensive way.’

Rodrik and Stantcheva, 2020

More…

The policy ideas proposed in this report are not short-term interventions to dampen the effects of the pandemic. Rather, they are important directions for the medium and longer term. Their goal is to address the fiscal challenges to maintain transfers and to start healing the inequality fractures that pre-existed and that have been exacerbated by Covid-19.

The challenges of inequality deepened by Covid-19 are big, and they need to be tackled at various levels. Rather than thinking about only ‘standard’ redistribution, or only labour market or education, these have to be considered jointly. Redistribution is key but it needs to be combined with appropriate ‘pre-redistribution’ – that is, with interventions to expand education and quality employment (so-called ‘good jobs’).

This would not only be a contribution to reduce inequality, but it would also eventually improve productivity. Without more equal access, technologies and resources remain bottled up in a few companies and among a few ‘elite’ groups of employees, mainly in urban metropolitan areas and do not trickle down to others. Many are left behind.

A post-Covid-19 world can be inspired by the idea of a ‘good jobs welfare state model’ that is built on three components:

- First, updated traditional welfare state policies that focus on education, social insurance, and progressive taxation.

- Second, a new focus on directly fostering good jobs and labour market experiences for all through labour market policies that partner with business and industrial or innovation strategies that target quality employment more explicitly.

- Third, better communication between governments and citizens.

A useful way to think of policy interventions is with the matrix. First, one can consider the income group that is mostly targeted by the policy: will it affect those at the very bottom of the income distribution, the middle class or the very top?

Second, one can think about the stage at which the intervention takes place: pre-redistribution policies directly influence how markets work and can usefully be split into pre-production policies and ‘production policies. Pre-production policies shape the endowments of individuals that they bring to the labour market, and their opportunities. Production stage policies influence the functioning of the labour market, including firms’ decisions. Post-production policies are ex post redistribution policies – that is, government transfers or progressive taxation.

Many traditional welfare states in Europe rely heavily on the first and third columns: fostering education and training to prepare people for the labour market on the one hand, and progressive taxes and transfers, as well as social insurance against unemployment, illness or disability on the other.

Production stage policies – except perhaps the minimum wage, collective bargaining regulations and labour protection – are not systematically geared towards reducing inequality and creating better jobs. They are instead targeted towards market competition, physical investment and R&D, along a traditional divide between ‘social policies’ to tackle inequality and economic policies to improve productivity, innovation and growth.

But such traditional welfare state systems are built on the assumption that (almost) everyone who wants a good job can find one. Covid-19 has shown very clearly what inequalities there are in the quality of jobs accessible to different groups and how unequal the opportunities are.

Good jobs, which were the pillar of the welfare state in past decades, have been disappearing. It is not possible to define what a ‘good job’ is in the absolute, as it depends on local circumstances and people’s preferences (for example, for flexibility).

Nevertheless, some clear criteria are safe and reasonable work conditions, sufficient pay that enables a good living standard access to benefits such as healthcare, childcare and pensions in the future, as well as adequate social insurance and some share of career opportunities and progress.

In a world in which middle-class good jobs are disappearing due to longer-run trends such as technological change and globalisation, and where shocks such as Covid-19 exacerbate the cleavages, there is a need to act on all three columns in a coordinated and comprehensive way. Inequalities are in part perpetuated by the production stage, when firms make innovation, employment and investment decisions without necessarily internalising the far-reaching spillovers on current and future employees or the communities in which they operate.

‘Inequalities in the Times of a Pandemic’

Author:

Stefanie Stantcheva (Harvard University)