#EconomicPolicy

#EconomicPolicy77

Contacts:

Hannes Mueller

Barcelona School of Economics

h.mueller.uni@gmail.com

Power-sharing agreements

Evidence of the potential to promote lasting peace in conflict-afflicted countries

Agreements made between former enemies in civil conflicts to share political power in the same government can have a significant impact in reducing the likelihood and intensity of violence. That is the central finding of new research by Hannes Mueller and Christopher Rauh. Comprehensive power-sharing agreements – which cover substantive issues made between parties that are engaged in a continuing discussion – are particularly successful in promoting lasting peace.

Looking at how different aspects of society evolve after an agreement, the study suggests that gender exclusion declines, as do rural-urban disparities. In general, the distributions of all resources shift in response and indices of democracy improve.

Institutions related to law enforcement and justice also seem to develop after agreements. Given that access to justice is most strongly associated with reductions in violence over the long run, agreements appear to build bridges beyond the immediate peace. Policy-makers and stakeholders would do well to mobilise resources and efforts to establish such agreements between warring factions.

Violent conflict is one of the main impediments to economic development and it had displaced over 100 million people by mid-2022, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Yet many conflict-afflicted countries seem to be stuck in a conflict trap with a number of self-reinforcing crises.

How can the international community help? One pathway to peace lies in power-sharing agreements after which the former enemies share political power in the same government.

Power-sharing agreements do not have a good reputation and, on first sight, this seems justified. The large majority of agreements are followed by violence within the next year.

But when evaluating the effectiveness of agreements, one has to consider the extreme circumstances under which they are usually agreed. Countries tend to find themselves in the middle of a conflict trap, which is characterised by cycles of violence. Blaming violence on the power-sharing agreement is akin to blaming health problems on a patient after heart surgery.

To study the effect of a power-sharing agreement one needs to compare like with like: two countries with equally high conflict risk of which one signs a power-sharing agreement and the other does not. Thanks to these researchers’ work on predicting conflict – which they update monthly on conflictforecast.org – they are able to construct this sort of artificial laboratory experiment.

In the new study, they find that the likelihood of violence drops sharply by 20 percentage points after a power-sharing agreement is signed. Also, the intensity of violence, measured in terms of battle deaths, falls by 60% after an agreement.

Not all power-sharing agreements reduce violence by the same amount. Comprehensive agreements – which cover substantive issues made between parties that are engaged in a continuing discussion – are particularly successful at reducing the likelihood and intensity of violence.

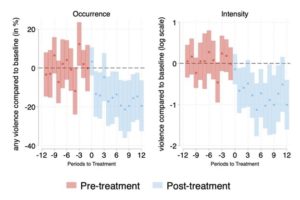

This is shown in Figure 1. The red bars show the difference between the matched countries with and without power agreements before the agreement. One can see that they are centred around zero, so there is no real difference between the countries in terms of the occurrence of violence (left) and the intensity of violence (right).

Figure 1: Occurrence and intensity of violence before and after a power-sharing agreement

Once the comprehensive agreement is signed, one sees how the blue bars drop below zero, showing that both the occurrence and intensity of violence drop for countries with comprehensive agreements. Moreover, the reduction in violence is lasting.

Even though power-sharing agreements are not a silver bullet, they do facilitate broader change in war-torn countries. Inequality across different dimensions can be conducive to conflict as it has the potential to generate frustration and act as a breeding ground for an ‘us against them’ narrative.

When looking at how different aspects of society evolve after an agreement, these results suggest that gender exclusion declines, as do rural-urban disparities. In general, the distributions of all resources shift in response and indices of democracy improve.

Institutions related to law enforcement and justice also seem to develop after power-sharing agreements. Given that access to justice is most strongly associated with reductions in violence over the long run, power-sharing agreements appear to build bridges beyond the immediate reductions in violence.

The conflict trap is very persistent. Countries that experience political violence suffer from widening cracks between groups and identities. These divisions are hard to reconcile, hampering economic growth and basic civil liberties.

As hard as it is to get parties to sit together and draft a document that specifies how power shall be shared, this research suggests that it is worthwhile. Despite many of these documents being agreed in bad faith, on average they reduce the likelihood and intensity of violence in the short run and facilitate broader institutional change for the better in the long run.

Policy-makers and stakeholders would do well to mobilise resources and efforts to establish dialogue and agreements between warring factions. Just because many of these power-sharing agreements apparently fail, it does not mean that these efforts are in vain.

Building Bridges to Peace: A Quantitative Evaluation of Power-Sharing Agreements

Authors:

Hannes Mueller (Barcelona School of Economics)

Christopher Rauh (University of Cambridge)