#EconomicPolicy

#EconomicPolicy78

Contacts:

Agustín Bénétrix: benetra@tcd.ie

Lorenz Emter: Lorenz.Emter@ecb.europa.eu

Martin Schmitz: Martin.Schmitz@ecb.europa.eu

Tackling tax evasion

New evidence of the impact of international agreements on cross-border deposits in tax havens*

An international agreement on automatic exchange of information (AEOI) by national public authorities has been effective in limiting cross-border deposits by less sophisticated investors seeking to evade taxes. But it might not be equally effective for those who are able to use more complex administrative structures, such as trusts and shell companies, to limit their tax liabilities.

These are the central findings of new research by Agustín Bénétrix, Lorenz Emter and Martin Schmitz. The results of their study imply that the AEOI has been more effective than earlier initiatives, but it remains incomplete as long as non-participating haven countries allow households to shift deposits. Hence, future policy initiatives should be aimed at widening the network of AEOI treaties, as well as increasing transparency about the ultimate ownership of investments by looking through corporate structures.

Tax havens are thought of as places that harbour assets from non-residents seeking to hide ownership to limit tax liabilities. Such international tax evasion not only reduces tax revenues and the effective taxation of the wealthy: it can also have an eroding effect on trust in state institutions and the tax system. Governments have tried to tackle the issue through several multilateral and bilateral policy initiatives.

The implementation of national and international tax transparency rules is at the heart of policy initiatives aimed at reducing tax evasion, which received renewed impetus after the global financial crisis and subsequent banking scandals. This included a push to fight tax evasion in the form of households’ undeclared foreign assets. The OECD and the EU were a driving force at the centre of it. The goal was to achieve a model for cross-country exchanges of information to limit evasion opportunities.

In 2009, the year in which G20 leaders issued the statement ‘The era of bank secrecy is over’, the first comprehensive agreement by the OECD was achieved. That information exchange agreement was a breakthrough towards more tax transparency. It became the international standard, with key features being a large set of signatory countries and information being shared internationally.

For this to take place, tax authorities had to make an information-sharing request. But these had mixed success. For one, they triggered reallocation of money to non-participating countries as deposits were shifted towards tax havens with the least number of bilateral exchange treaties. Moreover, their dampening effect on deposits in participating haven countries dissipated over time.

Against this background, the OECD pursued a more comprehensive coverage of tax information treaties through an automatic exchange of information (AEOI) system facilitated by the Common Reporting Standard (CRS).

These efforts, together with the adoption of the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) by the United States Congress in 2010, resulted in 119 jurisdictions being committed to the automatic exchange of information by 2022. In addition to expanding the network of treaties significantly, the key difference with the previous agreement was that the exchange of information became automatic instead of being on request.

The new study provides an evaluation of the AEOI using restricted data on deposits held in tax haven jurisdictions from the Bank for International Statistics (BIS) locational banking statistics. A key novelty compared with previous research is that the researchers use the non-publicly available breakdown of the non-bank counterparty sector. It distinguishes deposits held by households from those held by non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) and non-financial corporations (NFCs).

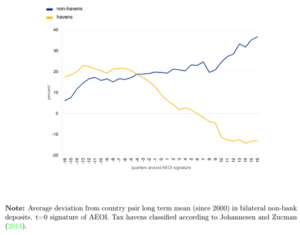

The findings suggest that the broader coverage of bilateral treaties and the threat of automatic information exchange significantly reduced cross-border deposits in tax havens by the non-bank sector residing in non-haven countries. In fact, the perceived threat associated with the implementation of the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) system materialised already before its implementation. Cross-border deposits by non-banks from non-haven countries in haven countries changed to a downward trend, while deposits among non-haven countries kept increasing (see Figure 1).

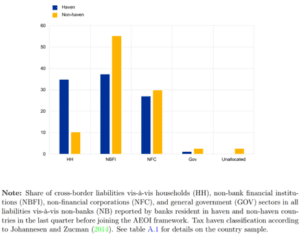

The non-haven household sector accounted for around 35% of deposits by non-banks held in haven countries before implementation of the AEOI (see Figure 2), making the household sector a key driving force for that trend change.

Bilateral household deposits responded with an estimated $70 billion withdrawal from the sample of haven countries. This was equivalent to a 28.5% reduction on signature of the AEOI legislation. Similarly, the broader non-bank sector exhibited a contraction of 12.5%, in line with previous research.

Applying the reported share of household deposits revealed by some of the haven countries to non-bank deposits in all tax havens reporting BIS locational banking statistics data during the sample period, suggests that of approximately $416 billion in deposits in tax havens, non-haven households withdrew approximately $119 billion. Importantly, this is a lower bound estimate as it is based on the subsample of tax havens reporting this information to the BIS. Moreover, they do not include other assets.

Furthermore, the research finds that the deterrent effects of the automatic exchange of information model on deposits is quite persistent, in contrast to the evidence presented by studies looking at exchange of information on request.

On the other hand, the new study reports evidence of significantly increasing deposits in haven countries from NBFIs resident in other haven countries after both countries joined the AEOI. This points to the possibility that networks of shell companies among haven countries became more elaborate after joining the AEOI. In turn, this might make it more difficult for tax authorities in non-haven countries to identify the ultimate owner of deposits due to the complex corporate structures employed.

Shell companies with beneficial owners related to the real owner are an example of such structures as the real owner would retain an element of control. Such a construction would help to circumvent AEOI treaties as the true identity of the ultimate owner of deposits would not be revealed to the tax haven resident banks and can thus not be submitted to tax authorities in the relevant non-haven countries.

Moreover, the study documents evidence of deposit shifting by the household sector. It finds that in the sample of haven countries reporting the detailed sectoral breakdown of deposits, households shifted deposits to havens that did not sign up to the AEOI framework (yet). However, there is no evidence of deposit shifting in the wider sample of haven countries that reports only the aggregate non-bank deposits, which is available for a larger group of countries. This highlights the importance of using granular data to evaluate the effects of AEOI.

Taken together, the new findings show that the implementation of automatic information exchange is effective in limiting cross-border deposits by less sophisticated investors. But it might not be equally effective for those who are able to use more complex administrative structures, such as shell companies, trusts, etc.

The results imply that the AEOI is more effective than earlier initiatives in that it is more persistent but remains incomplete as long as non-participating haven countries allow households to shift deposits. Hence, future policy initiatives should be aimed at widening the network of AEOI treaties, as well as increasing transparency regarding ultimate ownership of investments by looking through corporate structures.

Moreover, policy-makers should encourage making more granular data available for research purposes in order to strengthen the evaluation of the effectiveness of policy initiatives to fight tax evasion.

Automatic for the (Tax) People: Information Sharing and Cross-border Investment in Tax Havens

Authors:

Agustín Bénétrix (Trinity College Dublin)

Lorenz Emter (European Central Bank)

Martin Schmitz (European Central Bank)

Figure 1: Non-haven deposits in haven and non-haven countries around joining the AEOI

Figure 2: Share of liabilities vis-à-vis individual sectors

*The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Central Bank.