#EconomicPolicy

#EconomicPolicy73

#CovidEconomics

School Closures and the Spread of Coronavirus

Evidence from Germany finds little impact on infection rates

New research suggests that schools in Germany played only a limited role in the spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the summer and autumn of 2020. According to the study by Clara von Bismarck-Osten, Kirill Borusyak and Uta Schönberg (University College London), school closures do not appear to have had a containing effect on infections among either children or older generations. This is the case both in the summer, when infection rates were low, and during the pandemic’s autumn resurgence.

The findings suggest that the benefits of school closures may not outweigh the large costs in terms of the psychological and emotional development of children, as well as the indirect productivity penalties on parents and particularly mothers.

More…

In Germany, as in some other European countries, the share of children among Covid-19 cases increased around the same time as the new school year started in September 2020. Those events have often been linked to one another in the press – and the fear that schools constitute ‘hotspots’ of transmission has been fuelled by reports of outbreaks in schools.

But to guide policy, it is important to zoom out from the anecdotal or small sample evidence and identify the causal effect of school closures and re-openings on aggregate infections.

The new study tackles this problem by comparing the evolution of infection rates across 415 districts in Germany, where school holidays started at different times in the summer and autumn of 2020. A causal interpretation of such comparisons is possible as the timing of holidays was set years in advance, it was unaltered by the pandemic and it did not coincide with other containment measures.

The authors consider three events separately: the summer and autumn closures, and the summer re-openings. Comparing the dynamics of infection rates around each of them yields a consistent picture, pointing to little impact of schools.

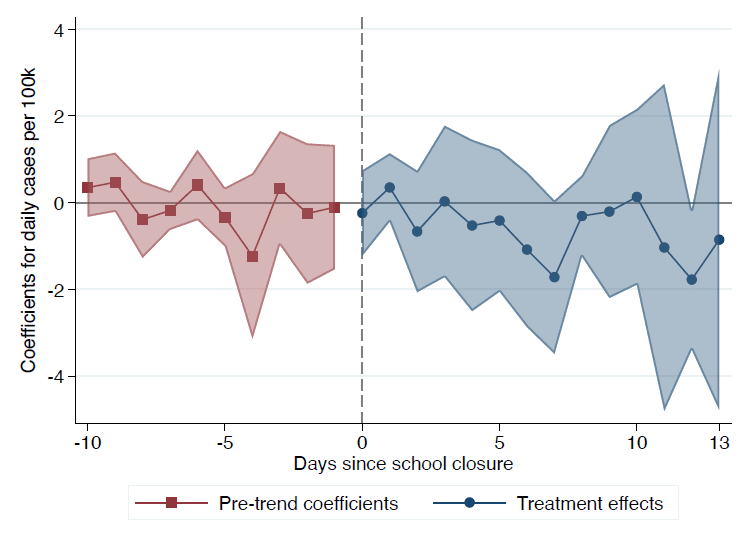

The summer school closures do not appear to have had a containing effect on infections in either the school population or older generations in a period of low infection rates. A similar finding for the autumn holiday closures suggests that school closures are no more effective at more advanced periods of the pandemic (with the raw data and authors’ estimates shown in Figure 1).

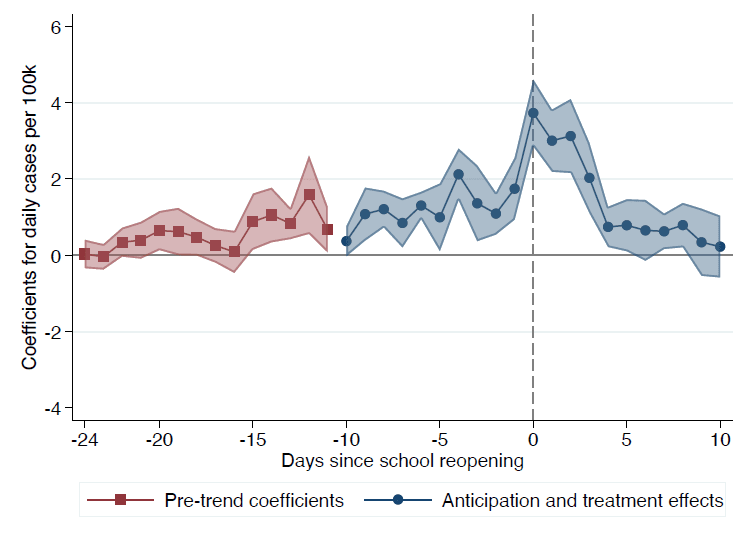

In line with their results on school closures, the authors find that concerns about the return to full schooling capacity after the summer holidays were unsubstantiated. Infections among children and adults did not rise with the start of the new academic year.

Instead, infections appear to have increased in the last weeks of the summer holidays and decline in the days after re-opening (see Figure 2). The researchers consider this to be best explained by a higher risk of infection of families returning home from their travels shortly before the summer holidays ended and increased testing.

The authors acknowledge that their study period precedes the emergence of allegedly more transmissible variants of the virus, such as the (British) B.1.1.7 strain, and precedes vaccination efforts – both of which are likely to affect the transmission risk in schools, although in opposite directions.

The authors conclude that while it is not their domain of expertise to explain why schools appear to play a subordinate role on the spread of SARS-CoV-2, epidemiological studies hint at several potential explanations.

One possibility is that the measures introduced in German schools to avoid contagion have been effective. Alternatively, children could be less susceptible to infection or less contagious than adults. Further epidemiological evidence on the relative role of such mechanisms would complement the policy implications of this study.

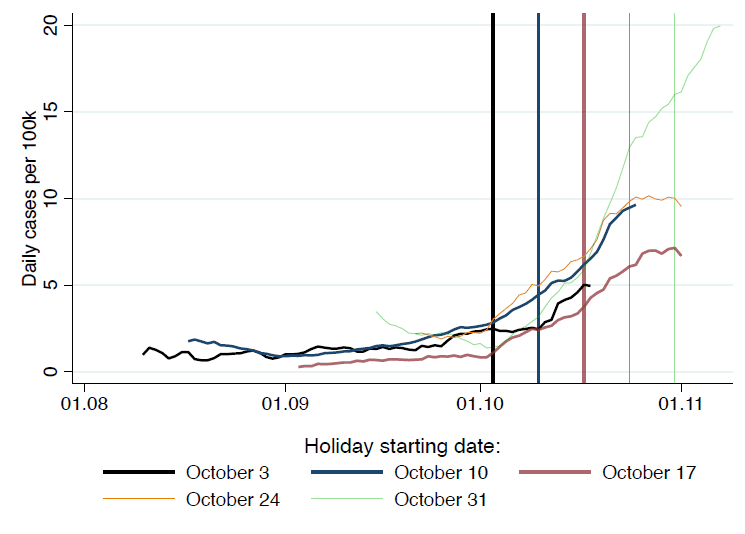

Figure 1: The impact of the autumn school closures on children aged 5-14

A: Raw data

B: Estimates

Panel A displays smoothed daily cases per 100,000 in the age bracket 5-14 years. Districts are grouped by the autumn holiday starting date. Panel B displays the corresponding estimates of the effects of school closure on the same outcome (blue dots), together with a test for parallel trends between districts where schools closed at different times (red squares). Districts in Bavaria are excluded in Panel B.

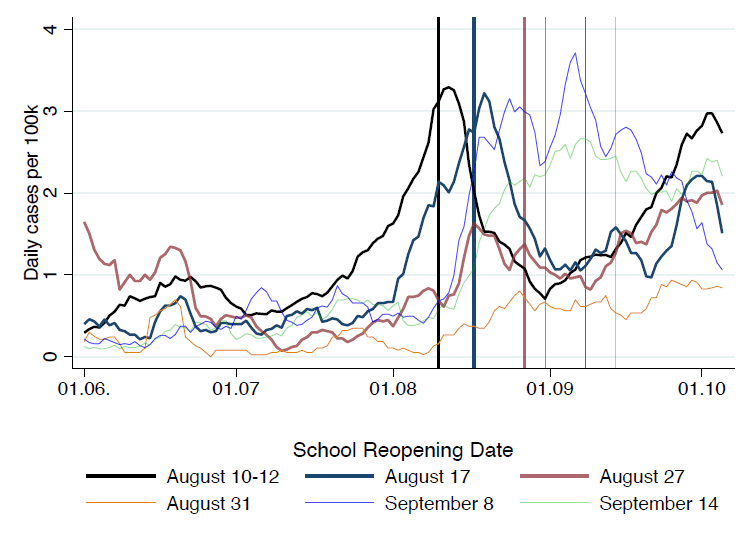

Figure 2: The impact of the summer school re-openings on children aged 5-14

A: Raw data

B: Estimates

Panel A displays the smoothed daily cases per 100,000 in the age bracket 5-14 years, grouping districts by the school re-opening date after the summer holiday. Panel B displays the corresponding estimates of the effects of school re-opening on the same outcome, including anticipation effects (blue dots), together with a test for parallel trends between districts where schools re-opened at different times (red squares). Districts in Bavaria and Baden Wuerttemberg are excluded in Panel B.

‘The Role of Schools in Transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Germany’

Authors:

Clara von Bismarck-Osten (University College London)

Kirill Borusyak (University College London)

Uta Schönberg (University College London)