#EconomicPolicy

#EconomicPolicy74

#CovidEconomics

Public Support for Mutual Economic Assistance within the EU

Survey evidence from the early days of the pandemic

At the height of the Covid-19 wave in Italy and Spain in March and April 2020, there was substantial public support for assistance packages for EU countries hit by economic decline as a consequence of the coronavirus crisis. Survey evidence from France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain, collected by Roel Beetsma and colleagues in those early days of the pandemic, indicates the potential public appeal of arrangements that are appropriately designed and well explained to citizens.

In particular, they find that support is broader when budgetary support is conditional on debt reduction in good times and spent in specific policy areas, notably healthcare. Support also increases when there is a role of the European Commission in terms of monitoring and providing guidance. And financing the assistance through a progressive tax increase is more popular than a flat tax increase.

More…

Despite bitter recriminations during the first corona wave and the resistance of the ‘frugal four’ EU members (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden) against a support fund, this study finds substantial public support for EU mutual assistance to countries affected by negative economic developments. Strong support is found even among the populations of traditional ‘net payer’ countries such as the Netherlands and Germany.

This finding contrasts with the observed political rhetoric, but can be explained by the ‘pre-political’ environment in which individuals were asked about such assistance: they had the opportunity to reason and form their own views about mutual assistance before concrete policy proposals were debated by politicians that seek the edges of polarisation.

The research was conducted using what is known as a conjoint experiment in which respondents from France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain were presented with hypothetical assistance packages for EU countries hit by either a temporary or a permanent economic decline. The survey was fielded in March and April 2020 at the height of the corona wave in Italy and Spain.

Packages were allowed to differ along six different dimensions: a prudent debt policy to be eligible for assistance; potential restrictions on how assistance could be spent; a possible monitoring role for the European Commission; whether some countries were allowed to benefit more than others; the possible impact on taxes; and the possibility of penalties for non-compliance with the programme conditions.

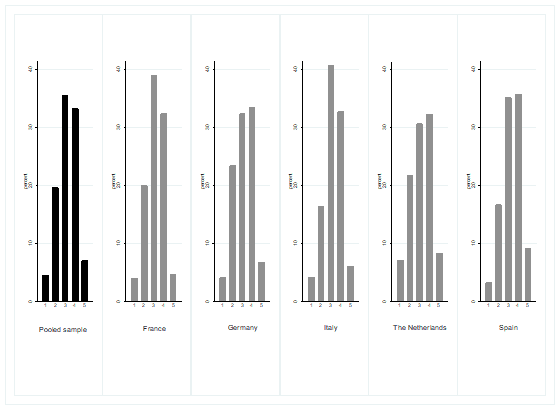

Average support for an assistance scheme is quite high, as Figure 1 shows. The likelihood of ‘somewhat in favour’ and ‘strongly in favour’ is for all countries (substantially) larger than that of ‘somewhat against’ and ‘strongly against’.

But one can do better than this average by endowing the assistance scheme with a well-chosen combination of features. The methodology makes it possible to estimate how variations along each of the individual dimensions affects support for the scheme. This helps in constructing a scheme that commands broad support in the EU.

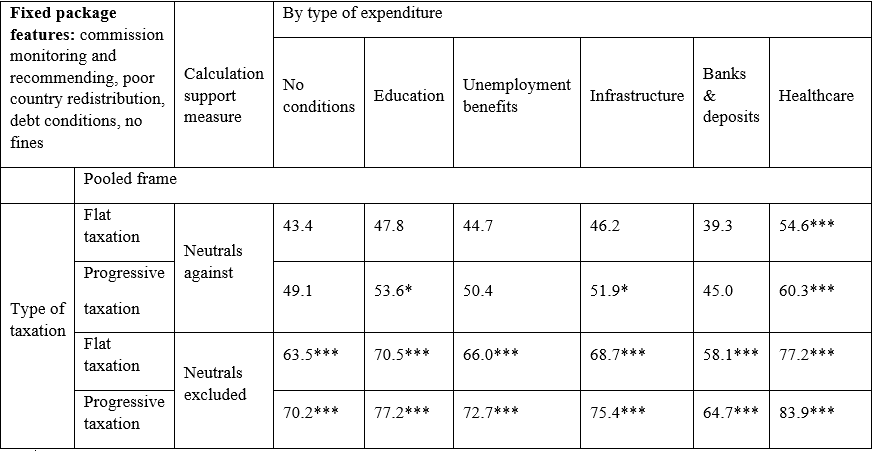

Indeed, a scheme that imposes conditions on debt policy, earmarks assistance for healthcare spending, has the Commission monitoring the scheme and making recommendations if needed, but does not envisage fines in the case of mistakes, allows for systematic redistribution to poor countries and is paid for by flat or progressive taxes can command majority support in all of our sample countries (see Table 1).

The broader lesson is that broad support for EU level mutual assistance arrangements may be possible provided that it is appropriately designed and well explained to citizens to allow them to form their personal view on the arrangement. This is important, because calls for a successor to the current NextGenerationEU will no doubt arise, especially when a new crisis strikes the EU.

Policy-makers would do well to be thinking through in advance what an acceptable mutual assistance scheme could look like. This will reduce the likelihood that the urgency of a new crisis presses them into adopting a badly designed scheme that is detrimental to popular support for EU solidarity.

Figure 1: Average degree of support for packages seen by respondents

Note: 1 = ‘strongly against’, 2 = ‘somewhat against’, 3 = ‘neutral’, 4 = ‘somewhat in favour’ and 5 = ‘strongly in favour’.

Table 1: Aggregate support (in %) varying spending area, type of taxation and support measure

Note: * = more than 50% support in 3 countries. ** = more than 50% support in 4 countries. *** = more than 50% support in all countries. No stars = more than 50% support in at most two countries. ‘Neutrals against’ counts individuals who are neutral about a package as opposing it.

‘What kind of EU fiscal capacity? Evidence from a randomized survey experiment in five European countries in times of corona’

Authors:

Roel Beetsma (Amsterdam School of Economics, University of Amsterdam; ACES; Copenhagen Business School; Netspar; CEPR; CESifo; and European Fiscal Board)

Brian Burgoon (Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Amsterdam, and ACES)

Francesco Nicoli (University of Ghent, and ACES)

Anniek de Ruijter (Faculty of Law, University of Amsterdam, and ACES)

Frank Vandenbroucke (Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Social Affairs and Healthcare of Belgium, and ACES)