#EconomicPolicy

#EconomicPolicy74

Ryan Banerjee and Boris Hofmann discuss how policy designed to help struggling firms survive crises may have increased the number of high-debt, low-productivity corporate zombies.

The Rise of Corporate Zombies

International evidence on the growing share of small, unproductive firms with limited growth prospects

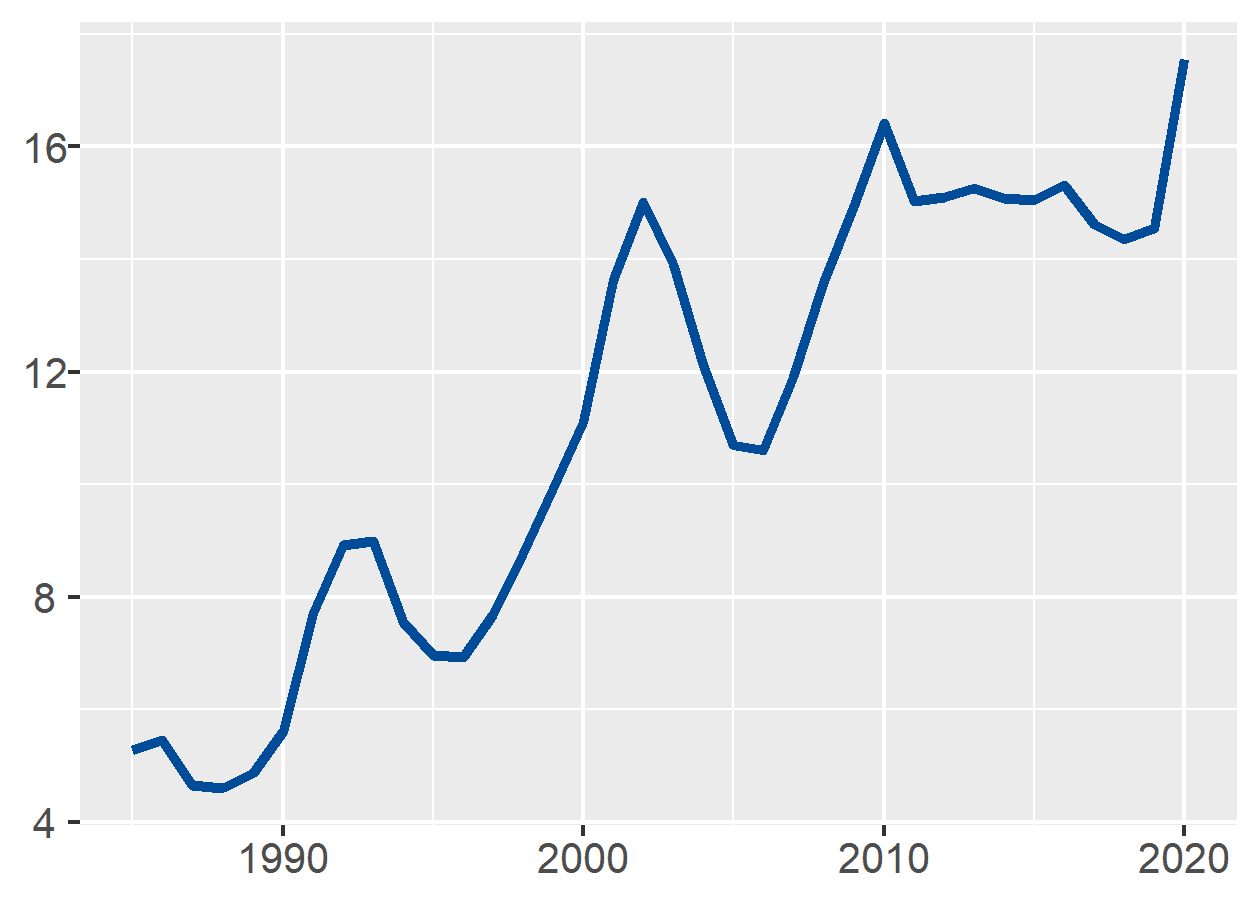

The share of so-called ‘zombie firms’ among listed non-financial companies in the advanced economies has risen dramatically over the past three decades – from just 4% in the late 1980s to more than 17% today. New research by Ryan Banerjee and Boris Hofmann examines the anatomy and life cycle of these weak and unprofitable firms with low stock market valuations; why and how they continue to survive; and the implications for the wider corporate sector and the economy.

The analysis shows that zombie firms are smaller, less productive and more leveraged, and they invest less in physical and intangible capital. They also shrink, selling their assets to pay back debts and cut employment. Their performance deteriorates several years before ‘zombification’ and remains significantly poorer than that of non-zombie firms in subsequent years. While the majority recover, most remain weak.

The findings also point to a growing army of enfeebled recovered zombies that underperform compared with healthy firms. Zombies often emerge in the wake of business cycle downturns and financial crises, as public authorities seek to support the economy but inevitably find themselves protecting low productivity businesses that otherwise would have gone to the wall.

More…

The new study analyses zombie firms, which are defined as unprofitable firms with low stock market valuation (reflecting low expected future profitability). The analysis takes a longer-run international perspective using firm-level data on listed non-financial companies covering 14 advanced economies and spanning three decades.

The results suggest that the share of zombie companies has increased considerably over the past three decades, rising from 4% in the late 1980s to more than 17% in 2020. The increase was not steady but occurred in the form of upward level shifts linked to major business cycle turning points and financial crises.

In terms of economic weight, zombie firms account for about 6-7% of all listed companies’ assets, capital and debt. If small unlisted firms are more likely to be zombified, as the analysis suggests, then the economic weight of zombies may be even greater. Indeed, among listed small and medium-sized enterprises, the share of assets, capital and debt sunk in zombie firms is around 40%.

Zombie firms are smaller, less productive and more leveraged, and they invest less in physical and intangible capital. They also shrink, selling their assets to pay back debts and cut employment. Their performance deteriorates several years before zombification and remains significantly poorer than that of non-zombie firms in subsequent years.

The analysis shows that the median zombie firm remains in this state for around seven years. Most zombie firms manage to recover, rather than exiting the market or remaining in zombie status. Yet closer inspection shows that those firms that do recover from zombification remain weak. They have a high probability of relapsing into zombie status, and their dynamism and productivity is significantly lower than that of firms that have never been zombies in their lives.

In other words, the zombie disease seems to cause long-term damage even for those that recover from it. The weakness and risks in advanced economy corporate sectors may therefore not be fully captured by headline figures of the number of zombie firms.

The findings in this study also have implications for the debate about the causes and consequences of zombie firms. With respect to the causes, the analysis suggests that zombies often emerge in the wake of business cycle downturns and financial crises, implying that smoothing the cycle and avoiding financial crises through effective macroeconomic stabilisation policy would also help to mitigate corporate zombification.

At the same time, financial pressure on zombies has dropped since the early 2000s, in part reflecting the easing effects of lower interest rates on financial conditions. This suggests a tricky trade-off for monetary policy between avoiding the genesis of new zombie firms in a downturn through easy monetary policy and sustaining zombie firms through low interest rates.

With respect to the wider consequences of zombie firms, the findings point to a growing army of enfeebled recovered zombies that underperform compared with healthy firms as a so far unrecognised consequence of the rise of zombie firms over the past three decades.

The congestion effects on non-zombie firms and the adverse effects on aggregate productivity also found by previous studies therefore probably not only capture the direct effects of zombie firms but also indirect effects through a growing number of weak recovered zombies.

Finally, the results underline the challenge facing public authorities when taking measures to contain the impact of the coronavirus recession on firms. The delicate task is to seek to shore up companies that would be viable in less extreme circumstances while at the same time not excessively dampening corporate dynamism by protecting already weak and unproductive ones. A firm’s viability should therefore be an important criterion for its eligibility for government and central bank support.

Zombie share increases with every cycle

In per cent

‘Corporate zombies: Anatomy and life cycle’

Authors:

Ryan Banerjee (Bank for International Settlements)

Boris Hofmann (Bank for International Settlements)